Worst Behaviour: Apparently You Can Use Slurs in Toronto Now

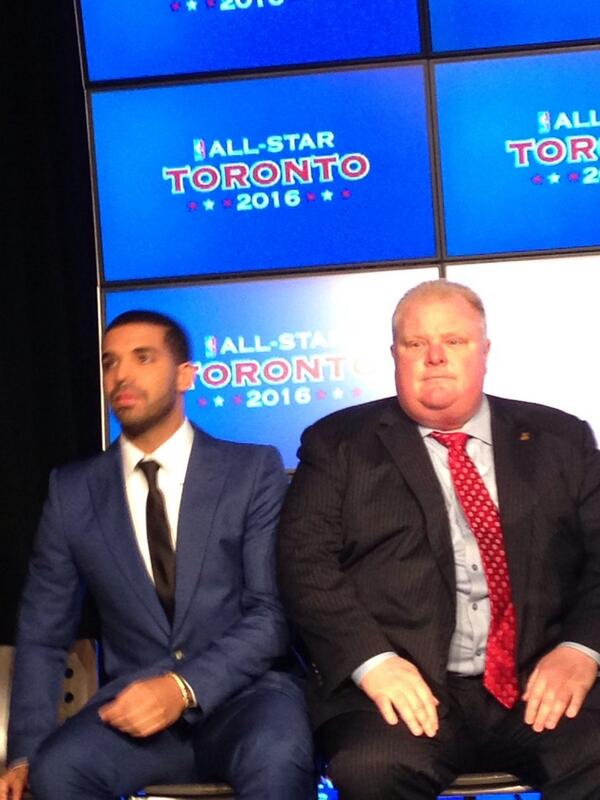

/Courtesy Rob Ford's Twitter.

By Anupa Mistry

From the outside, Toronto seems like a utopia: the world’s greatest rapper calls this city home (that’s Drake, if you haven't been paying attention), gay couples are free to get married, our healthcare system is beleaguered but subsidized, and our film festival is a barometer for Oscars. Torontonians are a happy clash of cultures; almost half the population are native speakers of another language. Vogue recently named our bustling Queen West the second hippest neighbourhood in the world. THE WORLD, YOU GUYS. VOGUE.

But in the tense run-up to the municipal election later this month, there’s been a lot of drama that exposes the conservative, xenophobic face of this city’s power elites. Two female candidates, both women of colour, have publicly come forward about incidents of basic bullying hate rhetoric directed at them online and IRL, some originating from self-professed members of the ill-defined, amorphous mob known as Ford Nation.

Ah yes, so Toronto also has this mayor, whom you’ve probably heard of— and definitely laughed at. Observers of all stripes, from newspaper columnists to sidewalk Sallys, attributed RoFo’s electoral success to a platform built on outer borough discontent on the narrative of a bougie, fast-gentrifying, pedestrian and cycle-friendly downtown core that stood in direct opposition to humble, hard-working, average people. Rob’s very suss M.O. was to paint the city’s core—Manhattanizing fast, in part because of pro-business types like himself—as a wealthy, artsy-fartsy enclave guzzling a disproportionate share of the City’s fiscal resources. It also skirted over his record of boorish racism and outright homophobia.

To Ford, courting poor and/or brown constituents meant offering fast fixes while consistently, singularly voting against social policies that could directly benefit those communities across the city. His drug scandal has disproportionately impacted the communities and families connected to his dealer transactions. He refuses to acknowledge Pride. When Rob’s team announced that his cancer diagnosis was the end to his appalling stewardship of this city, a lot of people breathed a sigh of relief; surely this would be the end of Ford for Toronto. But in stepped big brother Doug Ford, with his steely death stare and watchful bull terrier stance, to announce he’d be leveraging political sympathy and antipathy toward the Ford family to run in baby bro’s stead. The deplorable, beyond surreal saga of the tenure of Mayor Rob Ford just got even more unbelievable, and that means that coming municipal election on October 27th is as locally anticipated—and as crucial, on a macro-level—as Obama ’08.

But the impact of this election should be felt beyond just who gets voted mayor and who gets voted into ward councilor positions (analysis has shown that the incumbency rate is high, at 90%), because over the past two weeks things have gotten really ugly. Kristyn Wong-Tam, a queer Chinese-Canadian councillor for the bustling Toronto Centre-Rosedale ward, and something of a media sweetheart, recently received an anonymous letter (sent from a ‘Ford Nation supporter’) filled with a bunch of racist, sexist and homophobic crap. I don’t need to repeat what was said because it pretty much amounts to geospecific YouTube trolling—it’s the same unsophisticated, fear-filled wailing that dominates Internet comment sections.

Around the same time, mayoral candidate Olivia Chow, also Chinese-Canadian, began to experience and public acknowledge a rise in racist and sexist bullying, both online and IRL. A recent investigation by the Toronto Star found Chow’s team had removed almost 1,800 “racist, sexist and other offensive posts” since announcing her campaign in March. Just last week at a community debate, open mic time was sabotaged in order to publicly fling xenophobic garbage at Chow.

Chow and Wong-Tam aren’t the only women of colour currently campaigning for political office— young women like Munira Abukar, Idil Burale and Suzanne Naraine are also angling for councilor status—but they’re a significant minority amidst all of the dudely vibes of local governance. And Chow represents the first serious mayoral bid by a non-white candidate (period) since Carolann Wright-Parks ran in 1988.

Candidates of colour are consistently questioned on their capacity to lead or portrayed as pandering to their ethnic communities, when the reality is that everyone does it—even our Prime Minister. Add being a woman to that and you’ve erected a candidate specific hurdle that the straight white men running for office are able to gleefully glide past (because they make all the rules, duh).

The sexist, anti-ethnic, anti-diversity diversion that is plaguing Toronto’s recent municipal election isn’t just an overt warning sign that things are really fucking amiss at a very high level – it’s also a missed opportunity for political opponents to be leaders and rally around Wong-Tam and Chow and take an actual stand against the ideas that make this city great. No one is saying we have to vote in Chow or Wong-Tam or Burale or even Andray Domise, the phenomenal, Diddy-loving opponent facing off against the Ford family for Ward 2 councilor, but taking lateral strides to dissuade this kind of public harassment and discrimination wouldn’t just be setting a great example— it’d be upholding the Canadian Charter of Rights.

It’s important to note that this isn’t the first time a municipal election in Toronto was marred by hate: in 2010, mayoral candidate George Smitherman was the recipient of a ton of homophobic propaganda. The Ford bros. project of confusing hard-right stupidity for populism has stoked a fire in the rapidly diluting fabric of Old (Straight, White) Toronto, but directly attributing these ideas to some freak fringe of the city serves to distract from the fact that it’s this freak fringe that is in power. Despite the fact Toronto’s entire PR angle is that it’s this diverse utopia, mainstream institutions are pitifully indicative of that breadth. I mean, there’s a reason Drake had to go stateside to make it.

This piece was published in conjunction with The Hairpin, a place on the internet to read smart things, often by women.