Caste Your Vote: On Who's Allowed to Take Part

/By Desmond Cole

For the past six years, I’ve been hosting a public conversation about citizenship and inclusion as project coordinator of City Vote, an effort to extend municipal voting rights to all permanent residents of Canada. Support for the initiative, while on the rise, is still lukewarm at best. A 2013 poll determined that just over half of Toronto residents are opposed to the idea – an improvement from my early days on the campaign, but still surprising in a city where half of the inhabitants were born abroad. Last year Toronto city council endorsed a motion on permanent resident voting by 21-20, the narrowest of margins (the city has asked the province, who has the final say on the issue, to consider it).

City Vote supporters often ask me why people oppose giving non-citizens the local vote. While I don’t have a complete answer, I’m convinced that the presumed supremacy of our country’s British parliamentary democracy is an important factor. The British colonized this land and imposed their system of government, not only on all those who would come after them, but on the people who were already here. The treatment of Canada’s indigenous people as outsiders, as aspirants to British civilization, can teach us a lot about the struggle to enfranchise today’s non-citizen immigrants.

When people object to City Vote’s mission, they cite reasons they feel are practical and almost unquestionable: that non-citizens do not understand Canadian history, society and culture; that they have not demonstrated the proper loyalty; that giving non-citizens a vote would devalue the votes of citizens; that non-citizens value other things above voting, and therefore have no use for it.

All of these arguments were made about indigenous people as Canada established and amended its voting regimes. All of them rely on the apparent superiority of our current form of government, and by extension, the superiority of the white British elites who established it and used their power to categorize and regulate all non-whites.

When Canada held its first federal election in 1867, the country’s diverse indigenous inhabitants were not included; with few exceptions, the same was true for the provincial and municipal elections that preceded and followed Confederation. At first, most jurisdictions saw no need to make rules for prohibiting indigenous voters, who were assumed to be government property. But in 1865, British Columbia explicitly banned “Indians and Chinese” from voting in its elections. Even before Canada became a country, “Indians,” whose land the British had taken as their own, were excluded alongside “Chinese,” who had migrated to work or trade.

In 1885, Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, argued that Chinese people were not fit to vote because they possessed "no British instincts or British feelings or aspirations.”

“The Chinese are not like the Indians, sons of the soil. They come from a foreign country; they have no intent, as a people of making a domicile of any portion of Canada…. They are, besides, natives of a country where representative institutions are unknown, and I think we cannot safely give them the elective franchise.”

Macdonald’s fear that people raised under foreign governments couldn’t be trusted is, sadly, still with us. Likewise, for the indigenous “sons of the soil,” Macdonald and Parliament had created the Indian Act, to regulated their day-to-day existence. Parliament had also provided in 1868 for “voluntary enfranchisement”, a system which gave indigenous people the right to vote if they agreed to renounce their status as Indians. Professor Larry Gilbert has written that enfranchisement was “based on the theory that aboriginal peoples in their natural state were uncivilized. Once an aboriginal person acquired the skills, the knowledge and the behavior valued by civilized society, the aboriginal person might qualify for citizenship."

The arbitrary classification of today’s immigrants, who are encouraged to graduate into civilized Canadian citizens before being granted the privilege of voting, is nothing new. Rules about voting have been applied differently to different groups of people, and race has always been a defining factor.

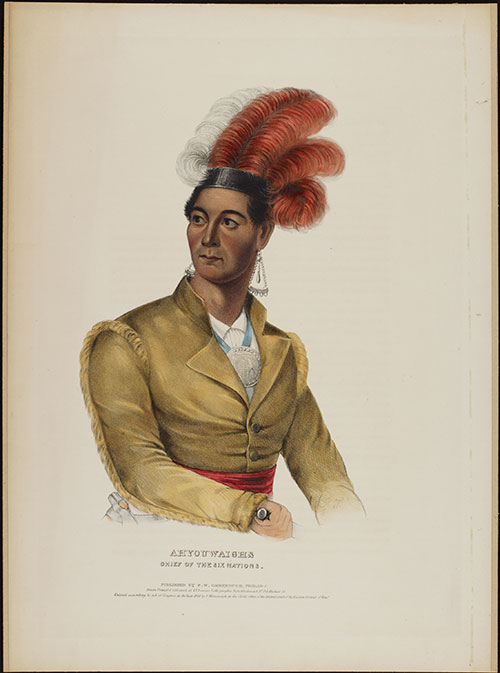

Ahyouwaighs, or John Brant. Painting by Charles Bird King.

Take the example of John Brant, an indigenous man who was elected to the Upper Canada Assembly, but whose election was subsequently nullified. As professor Veronica Strong-Boag wrote in 2002, “lease-holding, the proprietorship said to exist on Native reserves, was held not to count as property for the purpose of suffrage. Thus many of Brant's supporters were disenfranchised."

While indigenous people’s property rights were said not to count, the rights of white British subjects were upheld, and were sometimes even accepted in spite of the rules. As recently as 1969, British subjects who had lived in Canada for a year were eligible to vote, even South African citizens, although the country left the Commonwealth in 1961. Not by coincidence, South Africa has long contained Africa’s largest percentage of white inhabitants.

Today, there are no voting exemptions for property holders who are not Canadian citizens. As Ryerson professor Myer Siemiatycki has pointed out, Toronto’s municipal voter’s list includes property owners who are not residents of Toronto, but are still extended the right to vote, if they are citizens. Meanwhile, Siemiatycki notes, non-citizen property holders who do live here (and pay taxes here, and send their kids to school here, and otherwise contribute to and use the city) are excluded from voting at any level of government.

Before 1971, almost 80 per cent of immigrants to Canada were European – in other words, white. Between 2006 and 2011 more than 80 per cent of immigrants came from Asia, African, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.

As the makeup of our country has changed, so have restrictions for voting rights. For more than a century, proof of property rights, residency and taxation were good enough to allow British subjects to vote at the local level. Today, citizenship is the new standard for today’s mostly racialized immigrants. Yet non-citizen British subjects could vote in municipal elections until 1985 in Ontario; they retained the municipal vote in Nova Scotia until 2007.

We must also remember that other classes of non-citizen residents – temporary foreign workers, refugees, student visa holders, and people without any documentation – are not part of the current conversation to extend voting rights. Indeed, the mere mention of these groups, particularly undocumented people, is a non-starter for politicians.

So it was with indigenous people in the early days of Confederation, when politicians like Conservative George Foster had to assure his colleagues that enfranchisement was not meant for all indigenous people: “it is not the intention nor is it in the power of this Bill to enfranchise the wild hordes of savage Indians all over the Dominion.”

The fact that we can even have a conversation about non-citizen voting proves that we have made great strides towards a more inclusive country. But the continued resistance to change is based on an outdated and ultimately racist view that outsiders, particularly racialized ones, must prove their allegiance to a British system founded on assumptions of white supremacy.

During the 1885 debates on electoral reform, Liberal MP Peter Mitchell stated, “I would give to everyone who has assumed the same position as the white man, who places himself in a position to contribute towards the general revenues of the country, towards maintaining the institutions of the country the right to vote.” Although few today would be so blunt, the same attitude applies.