THE ELECTIONS ISSUE

Introduction: Or, Why I'll Miss the Fords

By Navneet Alang

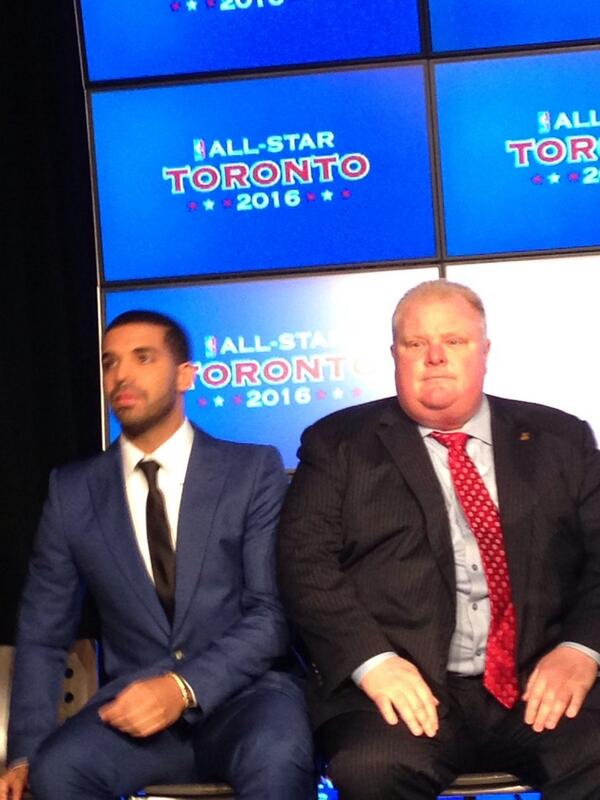

As I sit down to write this, Mayor Rob Ford is currently recuperating at home from what was surely a brutal course of chemotherapy. Meanwhile, Doug Ford—a man who just a short while ago couldn’t wait to blow the popsicle stand that is City Hall—has started his campaign to lead this city in a depressingly predictable fashion. John Tory and Olivia Chow continue to trade barbs and call it debate, while David Soknacki was forced to take his campaign of ideas out behind a Scarborough warehouse and put it out of its misery.

That we have arrived at this completely impossible-to-predict point does not bode well for Toronto. The catharsis that so many had longed for—whether a conspicuous repudiation of the Ford years, or a vindication of the Mayor—will never arrive. Instead, we’re set to live through a profoundly weird election: One in which the desire to avoid criticizing a man with a potentially fatal illness will result in a highly unsatisfying discussion of all but the most important issues at hand.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the Fords’ relentless debasement of government, avoiding discussion of their lasting effect on the city would be a huge loss. If Rob Ford’s doctors are able to treat his cancer successfully, it will be more than his family, his well-wishers, or his supporters who will rejoice. I will too—and not just for reasons of basic humanity. The fact is, we need the Fords.

I say this as an indictment of Toronto’s political establishment. For the past four years, Rob and Doug Ford have become symbols for whole swaths of this city that its media and its politicians either ignore, or simply pay lip service to. In them, we see the city that is dismissed and swept under the rug.

Opponents of Ford usually respond to this in the same way: that despite the Fords’ bluster of being “for the little guy,” their policies actually hurt the underprivileged. Worse still for some is the Fords’ significant wealth, which is out of the reach of many homeowners in the Annex or the Beaches, let alone “ordinary folks.” This is inarguably true—and irrelevant. What the Fords have inadvertently done is to force the city’s talking heads to deal with “the kind of people who support Rob Ford”—to confront their existence and their refusal to simply bend to the will of those in the know. The response has been telling.

“It’s not about the Fords per se; it’s about what their presence in our collective public sphere has allowed us to see and understand about race, class, and this city. ”

Almost every critique of Ford characterizes the mayor’s supporters as ignorant, obtuse, or just mean-spirited. The straightforward reasons that someone might support Rob Ford—his focus on keeping property tax rises low, his removal of the Vehicle Registration Tax, his plain-speaking approach, or that he seems like a regular, fallible guy—seem lost on far too many. Put more simply, there has been almost no attempt to cross the ideological chasm that separates the sort of person who condemns Ford from the person who stands behind him.

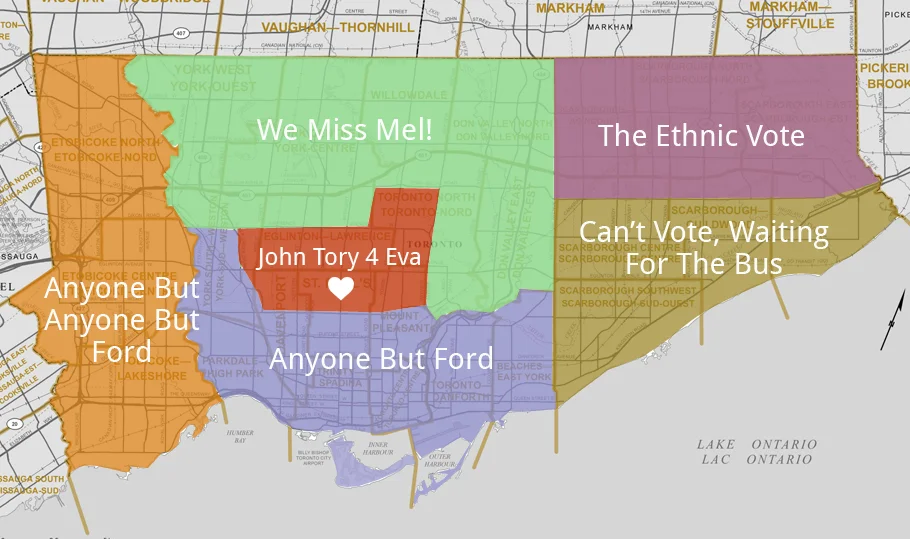

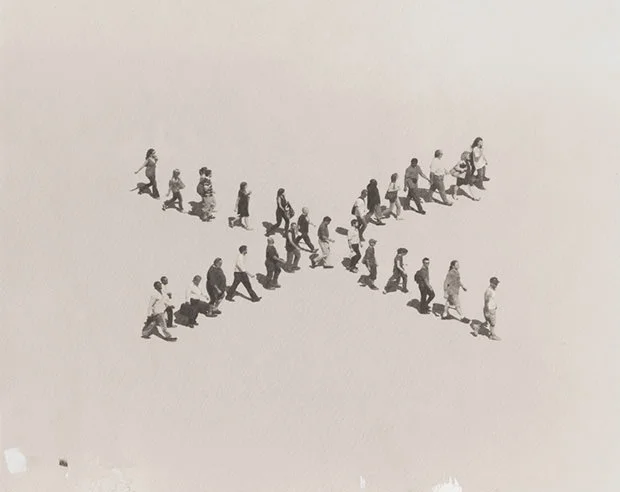

Taken alone, that would be unremarkable. But the division is all too frequently criss-crossed by the lines of race, class, income, and that looming urban-suburban divide that simmers in this city. There’s something both discomfiting and symbolic that the thousands of immigrants, racialized people, and lower income individuals who support Ford are seen as a mass of inexplicable, irrational people who “simply can’t see sense.”

In the circulation of ideas in Toronto, Ford has become a public symbol—a kind of avatar or proxy—for those people, even if practically he seems to work against actually representing their interests. His mere existence as Mayor, and the sheer visibility of his support, push marginalized people into the spotlight—at which point, their concerns and interests are dismissed as slavish, unthinking devotion to the cult of Ford. In simply being there, the Fords have been a barometer for how Toronto’s media and its cultural leaders deal with Toronto’s suburbs and marginalized peoples. It’s not about the Fords per se; it’s about what their presence in our collective public sphere has allowed us to see and understand about race, class, and this city.

Our mandate here at the Ethnic Aisle has always been to stand for, amplify, and provide space for those voices and perspectives that get erased in Toronto. Despite the fact that most of us believe the Fords are bad for Toronto’s racialized people, the past few years prove that there is much beyond the dynasty from Etobicoke when it comes to increasing representation, equity, and justice in this city.

To that end, over the next week, we’re going to be looking at Toronto’s coming election through our own eyes. From talking to some of Toronto’s visible minority candidates, to thinking about what it might mean to have a female, Chinese mayor, to extending the vote to permanent residents, we want to consider what this election says about the extent of Toronto’s diversity—and how we can get past the deeply odd situation in which the Fords are our most visible representatives as they are also our worst enemies.

Canada Issue // Fall 2015