Pride and (Gay) Prejudice

/By Canice Leung

I think every person can pinpoint a moment in their lives when they begin to view their parents not as the role models and heroes you automatically trust and believe because they told you so, but as people with feelings, flaws, opinions and ideas that make you think more, less, skeptically or maybe just differently about them.

That moment for me came when I was about 15.

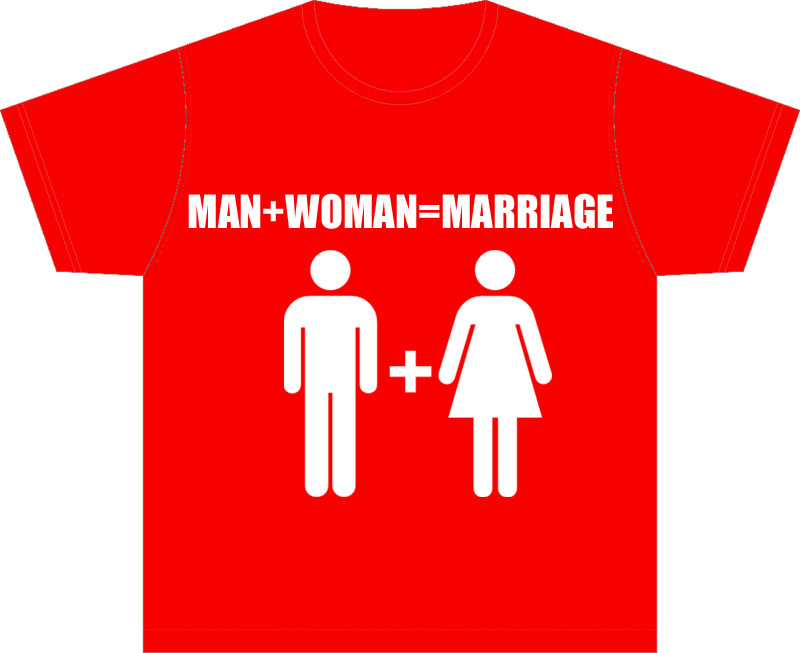

It was a Saturday morning (circa 2002/03, when the same-sex marriage debates and legal rulings were beginning in Ontario), and I had woken up and come down the stairs just as my parents came through the front doors. It wasn’t unusual for them to be up way before me — getting groceries, doing yard work, eating dim sum — but I immediately noticed the bright red T-shirts they had on. Here, to the best of my recollection, is what they looked like:

So I asked them, more rhetorically than anything, “Where have you been?”

“Down Yonge Street. Church organized it. Lots of people were there, hundreds.”

“And the shirts?”

“We were all wearing them. We matched!” they enthused.

“Oh.” That’s pretty much where the conversation ended, since I was too bleary-eyed to process exactly what the fuck they had gone and done, besides to think, WHATTHEFUCK. Also, I remember being miffed because they did not bring home dim sum leftovers.

Around the same time, I had a very good friend come out of the closet between periods at school. When he told me, he said so sheepishly, as though he expected my reaction (and that our other friends) to be one of scorn or revulsion. The disclosure seemed so unimportant, so immaterial to the dynamic our friendship that I just blinked a few times, smiled and said, “That’s cool, man. We’re going to be late for French.”

Between then and now, I also had a feminist awakening, a liberal awakening, all events that would set me further and further apart from my parents on the spiritual-political spectrum. It wasn’t in the way that kids instinctively want to be the opposite of their parents, but a real philosophical divide. The struggle that my parents (my dad, especially, who’d grown up poor) had faced as Trudeau-era, university student immigrants was intrinsically linked to that of LGBT folks, women and the poor. Couldn’t they see that?

(Tannis Toohey/Toronto Star photo)

These days, I often view my relationship with my parents through the Jason ‘Smiling Buddha’ Kenney lens. Up until May, the riding I’d lived in my whole life had been a Liberal stronghold, but the last few years have been a case study in how the Tories court an ethnic riding:

- Parachute in candidates with no qualifications other than having Chinese names. (N.B. candidate Chungsen Leung lost in 2008, but for what it’s worth, my parents voted for him, and every Chinese candidate before that.)

- Back policies that mirror the views of the socially and fiscally conservative population. Direct quote from my parents: “We’re voting Conservative because they oppose gay marriage.”

- Pander to them with symbolic gestures such as the redressing of the head tax. My mom was so deeply touched by this gesture, yet to my knowledge we have no relatives, distant or otherwise, who ever came to Canada while this law was in effect.

- Shake hands with a couple people from each community, maybe put on their ethnic dress.

- Sit back and win.

Anyone who doubted the efficacy of this strategy is probably a now-former Liberal MP. I hope someone’s writing a political science thesis on this.

So, it’s no surprise that the Chinese people of Richmond Hill helped swing the vote blue. My parents and many of their friends are an immigration minister’s wet dream: fundamental Christians (members of a 5,000-member Chinese-Canadian megachurch), affluent GTA suburbanites, double-income families that value hard work, education and pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. And since traditional Chinese values are pretty much Confucian values, in which filial obedience and child-production are paramount, gay marriage doesn’t fit into the Chinese social fabric. Religious or not, I believe your average Chinese person will always be closer to the Tories in social values than any Liberal or NDPer.

Add to this that their church is also active in politics. Their pastors have endorsed parties, candidates and particular legislations and, as the t-shirt indicates, encouraged other forms of activism such as protest and letter-writing. (Lest you think their church is a political anomaly, I should point out there are Chinese-Canadian megachurches just like it in every Asian-GTA burb: Markham, North York, Unionville, Scarborough, etc.)

My parents will probably read this, and I’m sorry, Mom and Dad. But like I said, this moment also marked the beginning of the period when I also came to appreciate (not just criticize) my parents — that even if I disagreed, they believed in their politics as ardently as I do mine. They weren’t just these pylons I yelled at and begged for rides and money… they came to Canada as university students speaking little English, carrying little money and carrying the fire to succeed. They also keep dinner time conversation interesting, if a bit combative.

Edited to add: This is not an apologia for my parents’ generation of Chinese-Canadians, but rather an explanation for why they think this way — it’s partly a generational thing carried over from their own upbringings — and a tribute to the political power that such a community can wield. I respect the empire/infrastructure my parents’ church community has built for its members, even if I disagree with the politics. And, in the battle over the ‘very ethnic‘ vote, the voices and experiences of the people in those communities are rarely heard from directly.