Thomson Park > Trinity Bellwoods

/By Shawn Micallef

First you hear the bass coming through the trees. Then you smell the food. As the Highland Creek trail leads into Morningside Park’s vast expanse of lawn, all the people appear, sometimes hundreds of them on a peak summertime weekend. They’ll be scattered over a few dozen picnics. Some will be playing games, like soccer or badminton, and one or two will have a generator powering a big sound system playing hip hop, reggae, maybe Motown. People dance, on the grass, in the sun. Couples linger under a tree or wander away slowly from the bigger group, trying not to be too obvious, perhaps disappearing into the forest for a spell. It’s Toronto, so you might catch a whiff of weed competing with the smell of charcoal briquette smoke. This is the most comfortable the city gets. Even when passing through alone on a bike ride or hike, the happiness is infectious.

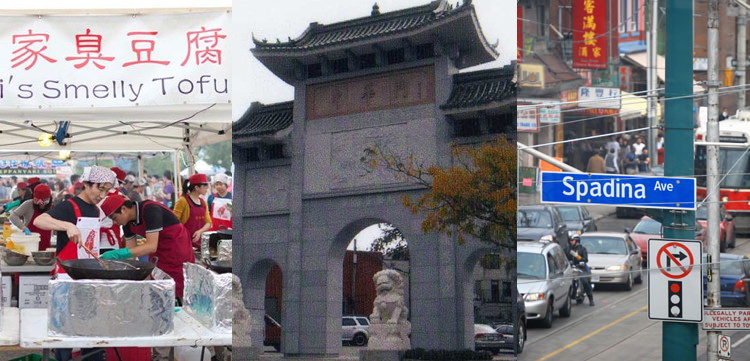

Long before cottage country, the automobile and the backyard pool took people away from city parks, Toronto’s waterfront and the interconnected ravine system into the suburbs were a summertime party. Variations of the scene at Morningside are repeated in T.E. Seaton Park adjacent to Thorncliffe Park, along Sunnyside Beach at Bluffers Park, and by the mouth of the Rouge River on the Pickering border. There are more picnickers still in Earl Bales Park in North York, or Thomson Memorial Park in Scarborough, and in the upper reaches of the East and West branches of the Humber River as it snakes through North Etobicoke and Rexdale. The waterfront and interconnected ravine network are cottage country for the uncottaged and embraced with vigour by Toronto’s various ethnic communities.

“The people are already in the parks – so now is the time to exploit how Canadians in the city use their natural spaces.”

A summer bike ride through the ravine system is an endless tour of picnics. If you didn’t know better it might seem like an organized festival (Ravine Day!), but it’s mostly ad hoc, organized individually by families and small groups. Even on the hottest day there will be those who dress formally: men in slacks and a dress shirt, women in flowing saris, the evolution of those great Edwardian photos in the archives of Toronto, where old Toronto WASPs dressed in their Sunday best while playing baseball or croquet in one of the ravines near Rosedale. It’s a Toronto sartorial tradition kept alive by “New Canadians,” and much more civilized than in overexposed Trinity Bellwoods park off Queen West, where deep-V t-shirts and armpit-exposing tank tops are the norm.

It’s interesting that just as Parks Canada is having trouble getting a new generation of Canadians to embrace the national park system, it happens naturally in the country biggest and densest urban centre. Despite a bit of a bureaucratic morass, Rouge Park is set to become Canada’s first urban national park. The people are already in the parks – so now is the time to exploit how Canadians in the city use their natural spaces.

That won’t happen entirely naturally: We’ll need new ways of transporting people, especially to parks outside the city boundaries. These places sometimes way too hard to get to and too often lack essential things like public washrooms. As more people move to Toronto, the ravine and park system we have will become increasingly critical to the quality of life here, for New Canadians and otherwise. That’s the way it’s always been and can continue to be, with a little help. The ravines give people living in urban landscapes, whether downtown or suburban, a connection to Canada’s founding myth of wilderness and rural landscapes.

Shawn Micallef is currently working on Accidental City, a documentary project on the Toronto ravines. Watch the teaser video here, complete with stunning drone footage of the ravines, and consider helping them reach their fundraising goal.