My Big Fat Greek Winnipeg

/Photographs by Andrew B. Myers

By Agapi Mavridis

Growing up in Winnipeg, I had the typical experience of many second-generation Canadians: immigrant parents with thick accents that were hard for my friends to understand, and a name whose pronunciation challenged even the most linguistically adventurous substitute teacher. Our religious practices were unknown to most people, and the foods my mother cooked were delicious memories of what she ate in her home country, and couldn’t be found in local supermarket freezers.

My family is loud, large and proud to be Canadian. We are also white.

I grew up in Winnipeg’s Greek community—a community so small that it didn’t even rank as its own ethnic group in the 2006 census results. Greeks were lumped into the category of “Southern European origins,” which made up only 6.5 per cent of the metropolitan area’s population. Nonetheless, I went to Greek school, learned how to Greek dance, and (most years) roasted a whole lamb or two in our backyard to celebrate Orthodox Easter, which came at a later date than that other Easter. Being of European descent, I carry with me all the white privilege granted to anyone who is Caucasian. Having said that, I’ve never identified as white; I’ve always felt that white is a term that didn’t apply to me. I always refer to myself as Greek Canadian when asked about my ethnicity.

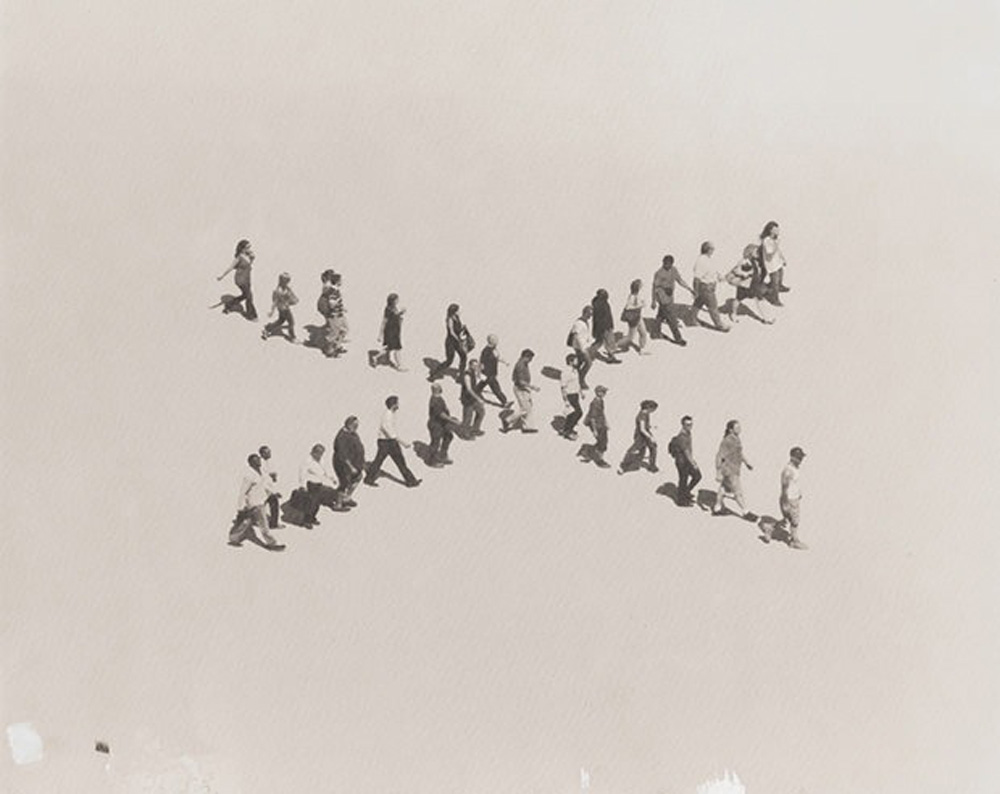

Statistics Canada defines second-generation as “individuals who were born in Canada and had at least one parent born outside Canada.” In 2011, just over 5,702,700 people were considered second-generation Canadians, or 17.4 per cent of the total population.

Until I moved to Ontario, I could never articulate why I felt I had more in common with fellow second-generation Canadians, regardless of ethnicity, than with other white Canadians. Within a few months of arriving I heard my friends using the terms “mungy cake” and “caker,” which I had never heard before. Eventually, a second-generation Italian friend I'll call Lisa filled me in: “Mangia-cake” began as Italo-Canadian slang for a non-Italian white person. One theory is that the name came from North America’s highly processed white sandwich bread, a pale imitation of crusty Italian loaves.

“To the Italians, it looked like they were eating plain white cake,” Lisa explained. The Italian word for eat is mangiare, so mangia-cake is literally “cake-eater.”

Put bluntly, mangia-cake is a derogatory term for the sort of whiteness that lacks any ethnocultural spark. It refers to the mythical white person whose family has been in Canada for so long that they have no ties to their country of origin and have lost any semblance of culture or ethnicity. To be mangia-cake is to be acultural, to be blank, to be stereotypically white. But being white does not automatically make someone a mangia-cake. In fact, anyone—including immigrants and their second-generation offspring—can act “like a caker.” What that translates to is almost always negative, namely behaving in a way that shows no passion for life, no hospitality or close connection to family, no appreciation for diversity, or awareness of anything beyond the tips of your fingers.

This is why I never felt white. I grew up in an ethnocultural community known for its hospitality, vibrancy, very recent immigrant heritage and unwavering Canadian pride. For me, white had become a synonym for mangia-cake, which I definitely was not.

But what does it mean to be white, anyway?

In a recent New York Times commentary, “What is Whiteness?,” American historian Nell Irvin Painter describes whiteness as being “on a toggle switch between ‘bland nothingness’ and ‘racist hatred.’” She suggests that “the inadequacy of white identity” in North America is rooted in “a history of multiplicity,” and reminds us of lingering attitudes from the 19th century when the Irish, Italians, Greeks and Jews were considered “inferior” white races.

This history helps explain the distinction I have always felt, this paradox of sticking out while fitting in. Visibly, I’m part of the majority—and I benefit from all the privilege that entails. Less visibly, I’m still part of an ethnic minority. This is what distinguishes the lived experience of so many second-generation European Canadians from that of the archetypal white Canadian community, living life as an “invisible minority.” You only have to watch My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the semi-autobiographical 2002 film written by and starring Nia Vardalos (a fellow Greek Winnipegger), to see this concept in action. In one scene, family patriarch Gus Portokalos compares his family to that of Ian Miller, his soon-to-be son-in-law:

“They different people. So dry. That family is like a piece of toast. No honey, no jam, just dry. My daughter ... gonna marry Ian Miller. A xeno (foreigner) with a toast family.”

Canadians are continually shaping how we define ourselves; it is a definition that often vacillates in the literature between the narratives of Aboriginal Peoples, white settler colonies and later immigrants. Concepts of whiteness as identity are not always part of the conversation, particularly when talking about diversity. But perhaps that’s the key to second-generation Canadians (and others) feeling connected to our national narrative. Perhaps the need to distinguish myself from the average “mangia-cake” Canadian comes from a need to be recognized as part of the diversity found within Canada’s ethnocultural communities; a very real need to be included in discussions of diversity, to be regarded as distinct and not to be swept under the white rug of sameness.